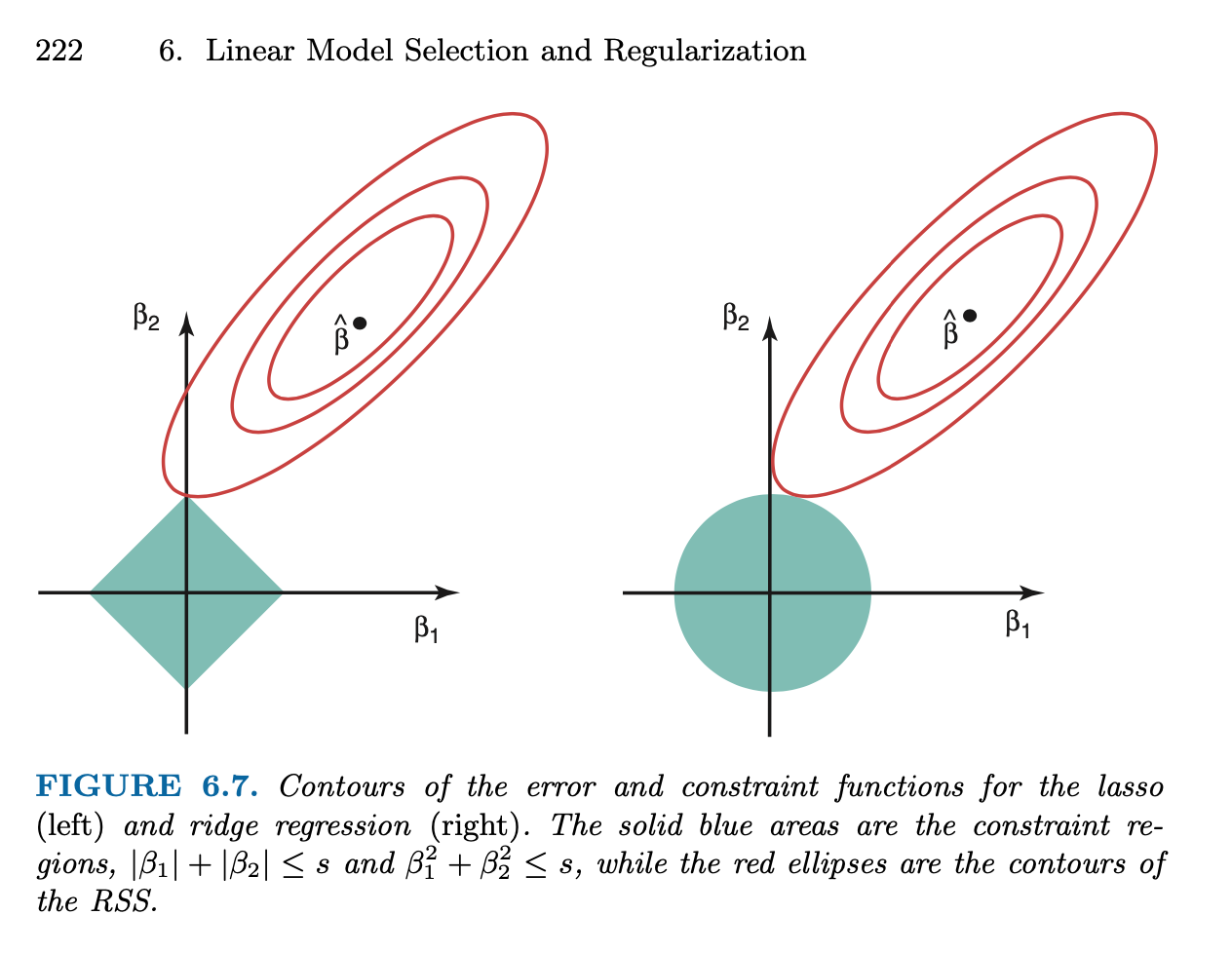

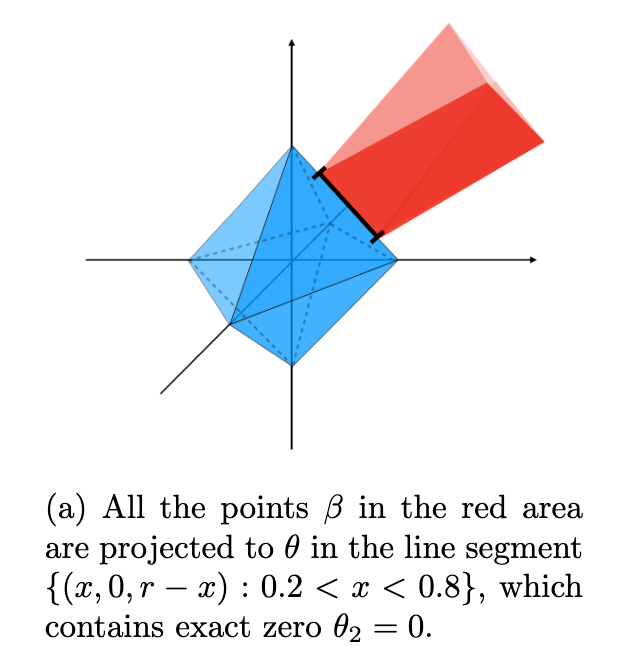

class: top, left, title-slide .title[ # Machine learning ] .subtitle[ ## High-dimensional regression ] .author[ ### Joshua Loftus ] --- class: inverse <style type="text/css"> .remark-slide-content { font-size: 1.2rem; padding: 1em 4em 1em 4em; } </style> # Benefits of shrinkage/bias ### In "high-dimensions" (p > 2) Shrinking estimates/models toward a pre-specified point --- ### Stein "paradox" and bias Estimating `\(\mu \in \mathbb R^p\)` from an i.i.d. sample `\(\mathbf Y_1, \ldots, \mathbf Y_n \sim N(\mathbf{\mu}, \sigma^2 I)\)` - The MLE is `\(\mathbf{\bar Y}\)` (obvious and best, right?) -- - [Charles Stein](https://news.stanford.edu/2016/12/01/charles-m-stein-extraordinary-statistician-anti-war-activist-dies-96/) discovered in the 1950's that the MLE is *[inadmissible](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admissible_decision_rule)* if `\(p > 2\)` 🤯 - The [James-Stein estimator](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stein%27s_example) **shrinks** `\(\mathbf{\bar Y}\)` toward some other point, any other point, chosen *a priori*, e.g. 0 `$$\text{MSE}(\mathbf{\hat \mu}_{\text{JS}}) < \text{MSE}(\mathbf{\bar Y}) \text{ for all } \mathbf \mu, \text{ if } p > 2$$` `$$\mathbf{\hat \mu}_{\text{JS}} = \left(1 - \frac{(p-2)\sigma^2/n}{\|\mathbf{\bar Y}\|^2} \right) \mathbf{\bar Y}$$` --- ### Shrinkage: less variance, more bias .pull-left[ <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-1-1.png" width="504" /> Solid points are improved by shrinking, hollow red points do worse ] .pull-right[ If `\(\bar Y\)` is between `\(\mu\)` and 0 then shrinking does worse In higher dimensions, a greater portion of space is *not* between `\(\mu\)` and 0 e.g. `\(2^p\)` orthants in `\(p\)`-dimensional space, and only 1 contains `\(\mu - 0\)` (*Not meant to be a [proof](https://statweb.stanford.edu/~candes/teaching/stats300c/Lectures/Lecture18.pdf)*) ] --- ## Historical significance Statisticians (particularly frequentists) emphasized unbiasedness But after Stein's example, we must admit bias is not always bad Opens the doors to many interesting methods Most (almost all?) ML methods use bias this way (Even if some famous CS profs say otherwise on twitter 🤨) --- ### Regularized (i.e. penalized) regression Motivation: If the JS estimator can do better than the MLE at estimating a sample mean, does a similar thing happen when estimating regression coefficients? -- For some penalty function `\(\mathcal P_\lambda\)`, which depends on a tuning parameter `\(\lambda\)`, the estimator `$$\hat \beta_\lambda = \arg \min_\beta \| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|^2_2 + \mathcal P_\lambda(\beta)$$` is "regularized" or shrunk (shranken?) toward values that decrease the penalty. Often `\(\mathcal P_\lambda = \lambda \| \cdot \|\)` for some norm Many ML methods are optimizing "loss + penalty" --- ### Ridge (i.e. L2 penalized) regression - Originally motivated by problems where `\(\mathbf X^T \mathbf X\)` is uninvertible (or badly conditioned, i.e. almost uninvertible) - If `\(p > n\)` then this always happens - Least squares estimator is undefined or numerically unstable For some constant `\(\lambda > 0\)`, `$$\text{minimize } \| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|^2_2 + \lambda \| \beta \|^2$$` **Shrinks** coefficients `\(\hat \beta\)` toward 0 Larger coefficients are penalized more (squared penalty) --- class: inverse, center, middle One common ML story: more flexible/complex models increase prediction accuracy by decreasing bias, but... # Bias *can* be good, actually ### Especially in higher dimensions --- class: inverse # Lasso regression #### Comparison to ridge regression #### Sparse models are more interpretable #### Optimality and degrees of freedom for lasso ## Inference #### ML/optimization finds the "best" model #### But is the best model actually good? --- class: inverse, center, middle # Interpretable ## high-dimensional regression ### with the lasso --- ### Lasso vs ridge - Generate some fake data from a linear model - Introduce lasso by comparison to ridge ```r library(glmnet) library(plotmo) # for plot_glmnet n <- 100 p <- 20 X <- matrix(rnorm(n*p), nrow = n) beta = sample(c(-1,0,0,0,1), p, replace = TRUE) Y <- X %*% beta + rnorm(n) lasso_fit <- glmnet(X, Y) ridge_fit <- glmnet(X, Y, alpha = 0) which(beta != 0) ``` ``` ## [1] 3 4 8 12 13 15 17 20 ``` Only 8 of the 20 variables have nonzero coefficients --- ### Lasso vs ridge: solution paths of `\(\hat \beta\)` .pull-left[ ```r plot_glmnet(ridge_fit, s = cv_ridge$lambda.1se) ``` <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-1.png" width="504" /> ] .pull-right[ ```r plot_glmnet(lasso_fit, s = cv_lasso$lambda.1se) ``` <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- ### Lasso vs ridge: L1 vs L2 norm penalties A simple `diff` to remember lasso/ridge is via the penalty/constraint (1-norm instead of 2-norm). Lasso is `$$\text{minimize } \frac{1}{2n}\| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 \text{ s. t. } \| \beta \|_1 \leq t$$` where `$$\| \beta \|_1 = \sum_{j=1}^p |\beta_j|$$` Lagrangian form `$$\text{minimize } \frac{1}{2n} \| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \beta \|_1$$` --- ## Lasso vs ridge: sparsity of solutions - For both ridge and lasso - Choose `\(\lambda\)` with cross-validation - Fit model on full data at the chosen `\(\hat \lambda\)` - Look at the estimate `\(\hat \beta\)` values... ```r cv_lasso <- cv.glmnet(X, Y) coef_lasso <- coef(lasso_fit, s = cv_lasso$lambda.1se) cv_ridge <- cv.glmnet(X, Y, alpha = 1) coef_ridge <- coef(ridge_fit, s = cv_ridge$lambda.1se) ``` Note: `lambda.1se` larger `lambda.min` `\(\to\)` heavier penalty --- ## Lasso vs ridge: sparsity of solutions ``` ## variable true_beta beta_hat_lasso beta_hat_ridge ## 1 1 0 0.000 0.0618 ## 2 2 0 -0.093 -0.1527 ## 3 3 -1 -1.082 -1.1544 ## 4 4 1 0.745 0.8530 ## 5 5 0 0.000 0.1161 ## 6 6 0 -0.154 -0.2495 ## 7 7 0 0.000 -0.0226 ## 8 8 1 0.967 1.0715 ## 9 9 0 0.000 -0.0977 ## 10 10 0 0.000 -0.0391 ## 11 11 0 0.000 0.0594 ## 12 12 -1 -0.737 -0.8383 ## 13 13 1 0.790 0.8056 ## 14 14 0 0.000 -0.0035 ## 15 15 1 0.868 0.9543 ## 16 16 0 0.000 0.0052 ## 17 17 -1 -0.748 -0.8540 ## 18 18 0 0.000 0.0474 ## 19 19 0 0.000 -0.0308 ## 20 20 -1 -0.898 -1.0079 ``` --- <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-8-1.png" width="70%" /> True values are solid black dots, lasso estimates are hollow red circles, ridge estimates are blue crosses --- ### High dimensional example <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-12-1.png" width="76%" /> --- <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-13-1.png" width="90%" /> --- class: inverse # Lasso: cool or extremely cool? - High-dimensional: `\(p > n\)` means we can't fit OLS But all is not lost! Penalized regression to the rescue - True model is sparse Only 21 of 200 variables have nonzero coefficients - Ridge estimates are dense All coefficients nonzero 😰 - Lasso estimates are sparse Nonzero estimates largely coincide with true model 😎 --- ## Lessons about sparsity ### Solving otherwise impossible problems *Curse of dimensionality* / NP-hard optimization (best subsets) / unidentifiable statistical estimation / overfitting vs generalization Need special mathematical structure like sparsity to make things tractable ### Sparsity helps with interpretation Easier to interpret 38 nonzero coefficients than all 200 --- ### Sparse models are more interpretable Usual linear model interpretation of coefficients If the conditional expectation function (CEF) is linear `$$f(\mathbb x) = \mathbb E[\mathbf Y | \mathbf X = \mathbf x] = \beta_0 + \sum_{j=1}^p \beta_j x_j$$` Then `$$\hat \beta_j \approx \frac{\partial}{\partial x_j} \mathbb E[\mathbf Y | \mathbf X = \mathbf x]$$` "Change in CEF *holding other variables constant*" Small set of **other variables** `\(\to\)` easy (human) understanding --- ### Why are lasso estimates sparse? - **Lagrangian form** `$$\hat \beta_{\text{lasso}}(\lambda) = \arg\min_\beta \frac{1}{2n} \| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \beta \|_1$$` - **Constrained form** `$$\hat \beta_{\text{lasso}}(t) = \arg\min_\beta \frac{1}{2n}\| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 \text{ s. t. } \| \beta \|_1 \leq t$$` Level sets `\(\{ \beta : \| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 = \text{const.} \}\)` are **ellipsoids** Level sets: `\(\{ \beta : \| \beta \|_1 = t \}\)` are **diamond thingies** (i.e. "cross polytope" or `\(L^1\)` ball) --- ## KKT optimality conditions Constrained optimization in multivariate calculus: - Switch to lagrangian form - Check stationary points (vanishing gradient) - Check boundary/singularity points - Verify feasibility (constraints satisfied) (Exam note: problems may use multivariate calculus like this) The [Karush-Kuhn-Tucker](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karush%E2%80%93Kuhn%E2%80%93Tucker_conditions) (KKT) conditions generalize these, useful for analysis of constrained optimization problems (i.e. almost all ML methods) -- more advanced, **not examinable** Recall: optimizer occurs at point of intersection between level sets of constraints and level sets of objective --- #### Why are lasso solutions sparse? ISLR Figure 6.7  --- ## Why are lasso solutions sparse? The `\(L^1\)` ball in `\(\mathbb R^p\)` `\(\{ x : \| x \|_1 = \text{const} \}\)` contains - `\(2p\)` points that are 1-sparse `\(x_j = \pm 1\)`, `\(x_{-j} = 0\)` - `\(\binom{p}{k} 2^k\)` points `\(k\)`-sparse with elements `\(\pm k^{-1}\)` - Higher dimensional edges/faces spanning (some) sets of these points, etc - Each of these is sparse, i.e. many coordinates are 0 -- The ellipsoid `\(\| \mathbf y - \mathbf X \beta \|_2^2 = \text{const}\)` *probably* intersects one of these *sharp parts of the diamond thingies* Solution to optimization problem is an intersection point --- ## Why are lasso solutions sparse? .pull-left[ At the point of intersection of the ellipse and the `\(L^1\)` ball, the normal vector of the ellipse has to be in the *normal cone* of the `\(L^1\)` ball (at the same point) Another intuition: consider projecting to the nearest point on the surface of the `\(L^1\)` ball (see figure) ] .pull-right[  From Figure 1 in [Xu and Duan (2020)](https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.01340) ] --- ### Optimality: stationary points - Of the **OLS** objective (uncorrelated residuals) $$ \frac{1}{n} \mathbf X^T ( \mathbf X \hat \beta - \mathbf y) = 0 $$ - For **ridge** (larger `\(|\hat \beta_j|\)` have larger resid. covariance) $$ \frac{1}{n} \mathbf X^T ( \mathbf X \hat \beta - \mathbf y) = - 2\lambda \hat \beta $$ - For **lasso** (resid. |covar| = `\(\lambda\)` if `\(\hat \beta_j \neq 0\)` and `\(\leq \lambda\)` otherwise) $$ \frac{1}{n} \mathbf X^T ( \mathbf X \hat \beta - \mathbf y) = - \lambda \text{ sign}(\hat \beta) $$ *Lasso treats predictors more "democratically"* --- ## Optimism / generalization gap **Recall**: for some `\(\text{df}(\hat f) > 0\)` (depends on problem/fun. class) `$$\Delta = \mathbb E_{Y|\mathbf x_1, \ldots, \mathbf x_n}[R(\hat f) - \hat R(\hat f)] = \frac{2\sigma^2_\varepsilon}{n} \text{df}(\hat f) > 0$$` #### Fairly general case For many ML tasks and fitting procedures `$$\text{df}(\hat f) = \frac{1}{\sigma^2_\varepsilon} \text{Tr}[ \text{Cov}(\hat f (\mathbf X), \mathbf y) ] = \frac{1}{\sigma^2_\varepsilon} \sum_{i=1}^n \text{Cov}(\hat f (\mathbf x_i), y_i)$$` --- ### Degrees of freedom: classic regression case If `\(\hat f\)` is linear with deterministic set of `\(p\)` predictors (or `\(p\)` basis function transformations of original predictors) then $$ \text{df}(\hat f) = p, \text{ so } \Delta = 2 \sigma^2_\varepsilon \frac{p}{n} $$ But if we do model/variable selection and use the data to choose `\(\hat p\)` predictors then *usually* $$ \text{df}(\hat f) > \hat p $$ And the more optimization / larger search this involves, it becomes more likely that $$ \text{df}(\hat f) \gg \hat p $$ --- ### Degrees of freedom: lasso case The "0-norm" (not really a norm) counts sparsity `$$\| \beta \|_0 = \sum_{j=1}^p \mathbf 1_{\beta_j \neq 0} = | \{ j : \beta_j \neq 0 \} |$$` e.g. for OLS with deterministic choice of variables `$$\text{df}(\hat \beta_\text{OLS}) = \| \hat \beta_\text{OLS} \|_0$$` **Surprisingly**, under fairly weak conditions on `\(\mathbf X\)` (columns in "general position"), for the lasso solution `\(\hat \beta(\lambda)\)` `$$\mathbb E[\| \hat \beta_\text{lasso}(\lambda) \|_0] = \text{df}(\hat \beta_\text{lasso}(\lambda))$$` **Solution sparsity is unbiased estimate of df** - like OLS case --- class: inverse # Choosing `\(\lambda\)` for lasso - Could use degrees of freedom combined with AIC, BIC, etc - Most commonly people use **cross-validation** ### Important note .pull-left[ `\(\hat \beta_\text{lasso}(\lambda)\)` at fixed `\(\lambda \quad \quad\)` vs ] .pull-right[ `\(\hat \beta_\text{lasso}(\hat \lambda)\)` at data-chosen `\(\hat \lambda\)` ] Different in general! e.g. Theoretical results about first may not apply to the second --- ## plot(cv.glmnet) and plot(glmnet) .pull-left[ ```r cv_fit <- cv.glmnet(X, Y) plot(cv_fit) ``` <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-14-1.png" width="504" /> ] .pull-right[ ```r plot_glmnet(lasso_fit, s = cv_fit$lambda.1se) ``` <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-15-1.png" width="504" /> ] --- class: inverse, middle, center # Inference ## for high-dimensional regression We have used regularization to avoid overfitting But this results in bias, e.g. `\(\| \hat \beta \|\)` smaller than true `\(\| \beta \|\)` Inference must correct for this somehow --- ## Approaches to inference - Debiased inference - Selective inference - Post-selection inference - Stability selection `R` packages for some of these Topic for future study? 😁 --- ## One example ```r set.seed(1) n <- 100; p <- 200 X <- matrix(rnorm(n*p), nrow = n) beta = sample(c(-1, rep(0, 20), 1), p, replace = TRUE) Y <- X %*% beta + rnorm(n) ``` Cross-validation plot (next slide) ```r beta_hat <- coef(lasso_fit, s = cv_lasso$lambda.min)[-1] vars <- which(beta_hat != 0) vars ``` ``` ## [1] 24 34 43 90 111 125 156 168 ``` **Idea**: since `\(\hat \beta\)` is biased by penalization, how about refitting OLS (unpenalized) using only these variables? --- <img src="07-1-highdim_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-19-1.png" width="504" /> --- ```r summary(lm(Y ~ X[,vars]-1)) ``` ``` ## ## Call: ## lm(formula = Y ~ X[, vars] - 1) ## ## Residuals: ## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max ## -1.598 -0.238 0.212 0.772 2.609 ## ## Coefficients: ## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) ## X[, vars]1 0.2373 0.0871 2.72 0.00771 ** ## X[, vars]2 -0.1335 0.0806 -1.66 0.10079 ## X[, vars]3 -0.1677 0.0768 -2.18 0.03160 * ## X[, vars]4 -0.3063 0.0817 -3.75 0.00031 *** ## X[, vars]5 -0.1351 0.0797 -1.70 0.09330 . ## X[, vars]6 0.1881 0.0808 2.33 0.02209 * ## X[, vars]7 -0.1481 0.0816 -1.81 0.07279 . ## X[, vars]8 -0.1530 0.0807 -1.90 0.06121 . ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ## ## Residual standard error: 0.81 on 92 degrees of freedom ## Multiple R-squared: 0.375, Adjusted R-squared: 0.32 ## F-statistic: 6.89 on 8 and 92 DF, p-value: 4.5e-07 ``` --- ## Looks good, time to publish! - Sparse, interpretable model - Some significant predictors - Decent `\(R^2\)` value showing predictive accuracy Pretty good... hey wait, what was this line in the code... -- ```r *Y <- rnorm(n) lasso_fit <- glmnet(X, Y) cv_lasso <- cv.glmnet(X, Y) ``` It was a trick 😈 🙈 model was *actually* fit on pure noise Classic inference methods don't work for *selected* models 😱 **Idea**: compute inferences (`summary`) on new validation data --- ### Lessons about high-dimensional regression - Can fit to noise, even with cross-validation - Theoretical results (advanced, not examinable) Lasso "performs well" (prediction error, estimation error, sparse support recovery) under various sets of sufficient conditions, derived/proven using KKT conditions and probability bounds (see SLS Chapter 11) Roughly: - `\(\mathbf X\)` has to be well-conditioned in some sense (null and non-null predictors not too correlated) - True `\(\beta\)` has to be sparse enough - Solution still generally includes some [false positives](https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-statistics/volume-45/issue-5/False-discoveries-occur-early-on-the-Lasso-path/10.1214/16-AOS1521.full) --- class: inverse #### Sparsity Useful simplifying assumption, especially in higher dimensions #### Lasso Penalized/regularized regression with the `\(L^1\)` norm #### Interpretation Sparse models are easier to interpret #### Model selection bias If we use the same data to (1) select a model and (2) compute tests / intervals / model diagnostics / etc, then those inferences will be biased (similar to overfitting)